From our anchorage at South Cape Fiord, we sailed about 50 miles (80 kilometers) east to Grise Fiord on the southeast corner of Ellesmere Island. The town looks across a body of water called Jones Sound to the south, toward Devon Island. “Grise Fiord is situated in a spectacular landscape, nestled beneath tall cliffs at the entrance to a beautiful fiord in the southern shores of Ellesmere Island at Jones Sound… Known as ‘Aujuittuq’ in Inuktitut [meaning “place that never thaws”] this warmly hospitable little hamlet is the northernmost community in Nunavut and Canada. Due to its remote and isolated location near the top of the world, it is a tightly knit community. The airstrip is short, so only medium sized aircrafts can land here, but when visitors arrive, they are always welcomed with big smiles. The word ‘Grise’ is Norwegian for ‘pig.’ There are no swine here, never were, but the Norwegian explorer Otto Sverdrup named this place ‘pig fiord’ [or, “pig inlet”] in 1899 because the loud sounds of walrus herds gathered here reminded him of grunting pigs. The Inuktitut name is more appropriate. It never completely thaws out, even when the sun shines constantly 24 hours a day from April through August.” — https://travelnunavut.ca/regions-of-nunavut/communities/grise-fiord/

The population of Grise Fiord is 143, of which 95% are Inuit. Ancestors of the Inuit, including Paleo-Eskimo, Pre-Dorset, Dorset and Thule peoples all lived in southern Ellesmere Island. Because of the harsh weather and lack of resources, the local Inuit abandoned the region around Grise Fiord sometime before 1700 A.D. “The modern Inuit community of Grise Fiord did not exist until 1953 when the Government of Canada forcibly relocated Inuit families here from their Nunavik home of Inukjuak in northern Québec. The High Arctic Relocation Program also happened to the Inuit people of present-day Resolute. The federal government formally apologized to the Inuit people for this harsh treatment in 2008. The transition was arduous because the climate is far more severe than northern Québec and the game animals are different. Fortunately, the Inuit people of Grise Fiord are excellent hunters, gifted seamstresses and resourceful, good-natured providers for their families.” — https://travelnunavut.ca/regions-of-nunavut/communities/grise-fiord/

Grise Fiord is one of only three populated places on Ellesmere Island. The town lies 1,160 kilometers (720 miles) north of the Arctic Circle, and is the northernmost civilian community in Canada. Wikipedia notes that “it is also one of the coldest inhabited places in the world, with an average yearly temperature of −16.5 °C (2.3 °F).” On our visit, towards the end of August, the temperature in the morning was close to freezing (32 degrees Fahrenheit or 0 degrees Centigrade).

The settlement of Grise Fiord is an extremely sad story of government geopolitical ambitions executed at an extremely high human cost. Before sailing into the bay at Grise Fiord, our expedition leader, a former policeman and ship captain in the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police), now retired and an experienced Northwest Passage and Canadian Arctic ship captain, told us the history of the town. It is a story that is still NOT taught in Canadian schools and only understood by the Nunavut locals and explorers (and some visitors) to the northern area of Nunavut.

“This community (and that of Resolute) was created by the Canadian government in 1953, partly to asset sovereignty in the High Arctic during the Cold War. Eight Inuit families from Inukjuak, Quebec (on the Ungava Peninsula), were relocated after being promised homes and game to hunt, but the relocated people discovered no buildings and very little familiar wildlife. They were told that they would be returned home after a year if they wished, but this offer was later withdrawn, for it would have damaged Canada’s claims to sovereignty in the area; the Inuit were forced to stay. Eventually, the Inuit learned the local beluga whale migration routes and were able to survive in the area, hunting over a range of 18,000 square kilometers (6,900 square miles) each year.” – Wikipedia

“The community of Grise Fiord was created in 1953 when the Canadian government relocated 3 families from Port Harrison (now Inukjuak), Quebec. They were accompanied by one family from Pond Inlet who were to ease their adjustment to life in the High Arctic.” — http://toolkit.buildingnunavut.com/en/community/load/B17AC5F3-8273-41EC-9982-A1F700F2D229

In 1993, the Canadian government held hearings to investigate the relocation program. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples issued a report entitled The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953–55 Relocation, recommending a settlement. The government paid 10 million Canadian dollars to the survivors and their families and gave a formal apology in 2010.

“The houses are wooden and built on platforms to cope with the freezing and thawing of the permafrost. Hunting is still an important part of the lifestyle of the mostly Inuit population. Quota systems allow the villagers to supply many of their needs from populations of seals, walruses, narwhal and beluga whales, polar bears and muskox.” — Wikipedia

Larry Audlaluk was a 3-year-old toddler when he and his family (including 6 older siblings) were relocated by the Canadian government from Inukjuak on Hudson Bay, Canada, to Grise Fiord in 1953; his father died 10 months later. Larry’s life story, What I Remember, What I Know: The Life of a High Arctic Exile (2020), provides a detailed personal account of the danger and death that they faced. His parting words to us at the monument were a wonderful sentiment, “after you leave Grise Fiord, please wake up each day and enjoy the sunlight and think of me.” (Note that Grise Fiord, way above the Arctic Circle at N 76º 25′ W 82º 54′, has no sunlight for half the year.)

“The High Arctic relocation is the subject of Zacharias Kunuk’s film Exile. The film was produced by Isuma, who also released Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, the first feature film ever to be written, directed and acted entirely in Inuktitut. The High Arctic relocation is the subject of the film Broken Promises – The High Arctic Relocation by Patricia Tassinari (NFB, 1995). The relocation is also the subject of Marquise Lepage’s documentary film (NFB, 2008), Martha of the North (Martha qui vient du froid). This film tells the story of Martha Flaherty, granddaughter of Robert J. Flaherty, who was relocated at 5, along with her family, from Inukjuak to Grise Fiord (Ellesmere Island).” — Wikipedia

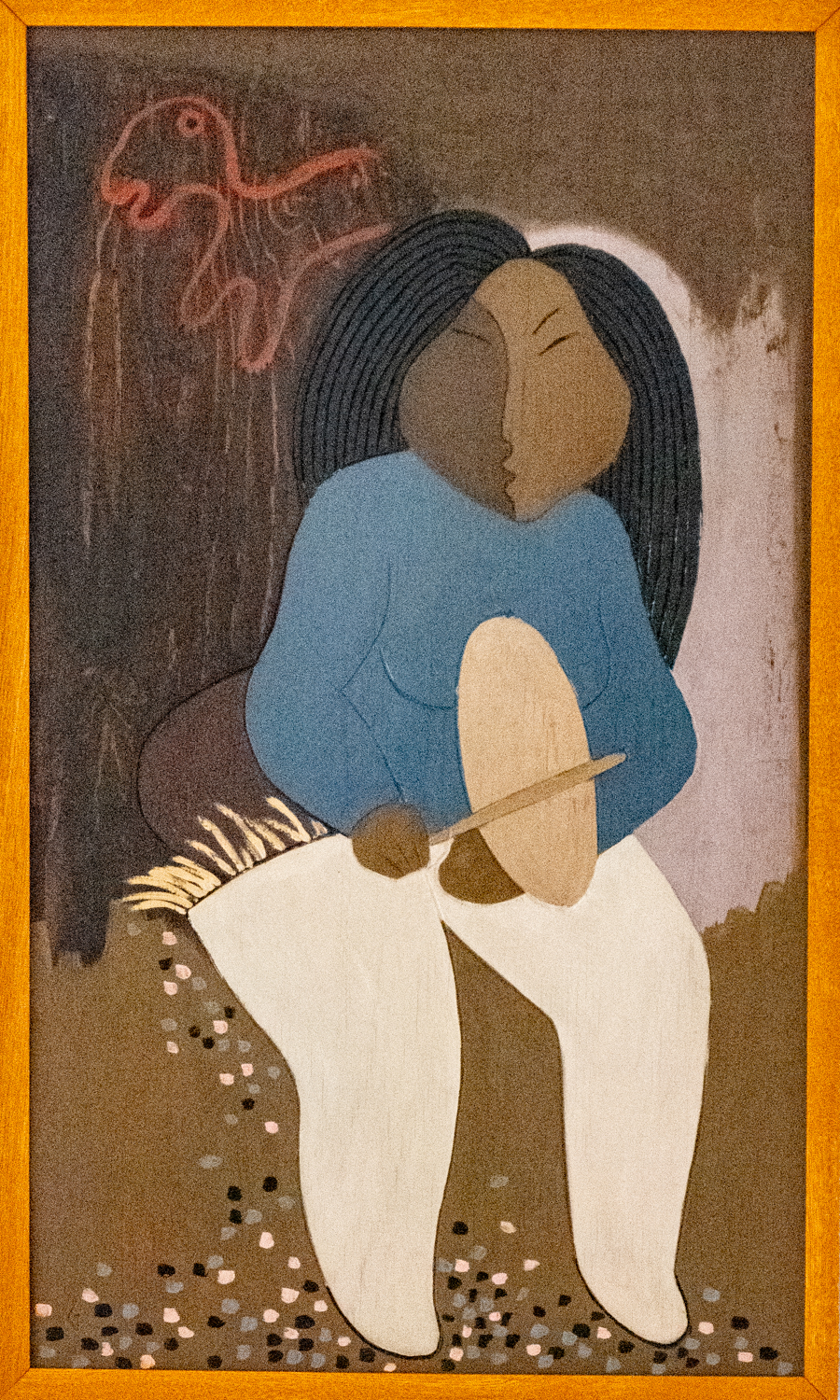

“In 2009, artist and Grise Fiord resident Looty Pijamini was commissioned by Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated to build a monument to commemorate the Inuit who sacrificed so much as a result of the Government’s forced relocation programme of 1953 and 1955. Pijamini’s monument, located in Grise Fiord, depicts a woman with a young boy and a husky, with the woman somberly looking out towards Resolute Bay. Amagoalik’s monument, located in Resolute, depicts a lone man looking towards Grise Fiord. This was meant to show separated families, and depicting them longing to see each other again.” – Wikipedia

Looking at the photograph, one asks, “why are all those guys climbing all over the truck and looking in?” (it’s the same question we asked from ashore). The purchaser didn’t think it was a funny story, but the townspeople and we did. Apparently, when the truck was loaded onto the barge, someone, somehow, (accidentally) locked the keys in the truck. So, until they figured out how to open the truck, it wasn’t going anywhere. Note that the purchaser, one of the men in town, bought it as a present for his dad.

Wikipedia has a more extensive article on the “High Artic relocation” of 92 Inuit from northern Quebec Province to Ellesmere Island to serve as “human flagpoles” to help Canada assert its sovereignty in the Far North during the Cold War (1953-1955), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Arctic_relocation

“The High Arctic relocation (French: La délocalisation du Haut-Arctique, Inuktitut: ᖁᑦᑎᒃᑐᒥᐅᑦᑕ ᓅᑕᐅᓂᖏᑦ, romanized: Quttiktumut nuutauningit ) took place during the Cold War in the 1950s, when 92 Inuit were moved by the Government of Canada under Liberal Prime Minister Louis St. Laurnet to the High Arctic.

“The relocation has been a source of controversy: on one hand being described as a humanitarian gesture to save the lives of starving indigenous people and enable them to continue a subsistence lifestyle; and on the other hand, said to be a forced migration instigated by the federal government to assert its sovereignty[in the Far North by the use of “human flagpoles”, in light of both the Cold War and the disputed territorial claims to the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Both sides acknowledge that the relocated Inuit were not given sufficient support to prevent extreme privation during their first years after the move.

“In August 1953, seven or eight families from Inukjuak, northern Quebec (then known as Port Harrison) were transported to Grise Fiord on the southern tip of Ellesmere Island and to Resolute of Cornwallis Island. The group included the family of writer Markoosie Patsaug. The families, who had been receiving welfare payments, were promised better living and hunting opportunities in new communities in the High Arctic. They were joined by three families recruited from the more northern community of Pond Inlet (in the then Northwest Territories, now part of Nunavut), whose purpose was to teach the Inukjuak Inuit skills for survival in the High Arctic. The methods of recruitment and the reasons for the relocations have been disputed. The government stated that volunteer families had agreed to participate in a program to reduce areas of perceived overpopulation and poor hunting in Northern Quebec, to reduce their dependency on welfare, and to resume a subsistence lifestyle. In contrast, the Inuit reported that the relocations were forced and were motivated by a desire to reinforce Canadian sovereignty in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago by creating settlements in the area. The Inuit were taken on the Eastern Arctic patrol ship CGS C.D. Howe to areas on Cornwallis and Ellesmere Islands (Resolute and Grise Fiord), both large barren islands in the hostile polar north. While on the boat the families learned that they would not be living together but would be left at three separate locations.

“In Relocation to the High Arctic, Alan R. Marcus proposes that the relocation of the Inuit not only served as an experiment, but as an answer to the Eskimo problem. The federal government stressed that the Eskimo problem was linked to the Inuit’s reluctance to give up their nomadic ways in areas that were supposedly overpopulated and went so far as to provide detailed accounts of poor hunting seasons and starvation within the Inukjuak area as a direct result of over-population. However, the federal government knew the area in question was in the midst of a low trapping season due to the end of a four-year fox cycle.

“The families were left without sufficient supplies of food and caribou skins and other materials for making appropriate clothing and tents. As they had been moved about 2,000 km (1,200 mi) to a very different ecosystem, they were unfamiliar with the wildlife and had to adjust to months of 24-hour darkness during the winter, and 24-hour sunlight during the summer, something that does not occur in northern Quebec. They were told that they would be returned home after two years if they wished, but these promises were not honoured by the government.

“The relocatees included Inuit who had been involved in the filming of Robert J. Flaherty’s film Nanook of the North (1922) and Flaherty’s unacknowledged illegitimate son Josephie. However, Flaherty had died in 1951, prior to the relocation. Eventually, the Inuit learned the local beluga whate migration routes and were able to survive in the area, hunting over a range of 18,000 km2 (6,950 sq mi) each year.” — Wikipedia

The article concludes with a detailed discussion of the re-evaluation of the move. In summary, in 1993, the Canadian government held hearings to investigate the relocation program. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples issued a report entitled The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953–55 Relocation, recommending a settlement that was done in 2010, including an apology and the payment of 10 million Canadian dollars to the survivors and their families.

Legal Notices: All photographs copyright © 2023 by Richard C. Edwards. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. Permission to link to this blog post is granted for educational and non-commercial purposes only.